Beyond the Six String Nation #24: Mythologizing Geography

Griffin-Ondaatje-Rutledge-Kristmanson-Cooder

This post has been brewing in my head for more than a week and, to be honest, I wasn’t sure how I was going to weave the threads together because it’s hard to tell where one begins and the other ends. Coincidences can be like that (and I have a doozy I’ll share another time that’s a great example). But my subtitle today is giving me a hint so that’s where I’ll start and hopefully it all comes together by the end… if it is an end. You know, circles within circles and all that.

When I put those five names you see in the subtitle into Google, I only get hits for the author and filmmaker Griffin Ondaatje, with the other three crossed out by the search engine for not matching but (apart from this paragraph) this post has nothing to do with Griffin Ondaatje. Still, all of those names are connected in various ways. Perhaps if you now put those five names into Google you’ll come right back to this post – my gift to search. Now, I do know Griffin a little bit because we grew up in the same neighbourhood – our backyards each facing onto the greenbelt path that ran between our streets in Don Mills. I was friends with his older sister, Quintin – though not as close as my sister, Annalisa, was. They were best friends. Their father, of course, was the author Michael Ondaatje – and our two families knew each other mostly through that initial connection between Annalisa and Quint, though other bonds grew over the years. Later, as I ventured into the Toronto poetry scene through mentors like Christopher Dewdney, Katherine Govier, David Young and Sarah Sheard, I found myself a guest at Michael’s then-new midtown house for readings and performances by Nobby Kubota, bp nichol, the rest of the Four Horsemen and other visiting writers. Later still, I found myself living in that house. But, in case you hadn’t already suspected I was digressing with the whole Griffin thing, I digress – though that summer living on Lawton Blvd. will come back in a big way later on (or perhaps sooner – like I said, I still don’t have a clear handle on where this tale begins and ends). In fact, let me tease it a little bit here…

…Last week, my friend (and pivotal Six String Nation supporter) Dr. Mark Kristmanson, resumed his Substack, A Diary of Canadian Biography, with a post entitled Fly With The Plumes. In it, he recounts a 2003 late stage interview for a senior director position with the National Capital Commission in Ottawa. Taking him by surprise, the president of the hiring committee asks:

“What is your favourite Canadian novel?”

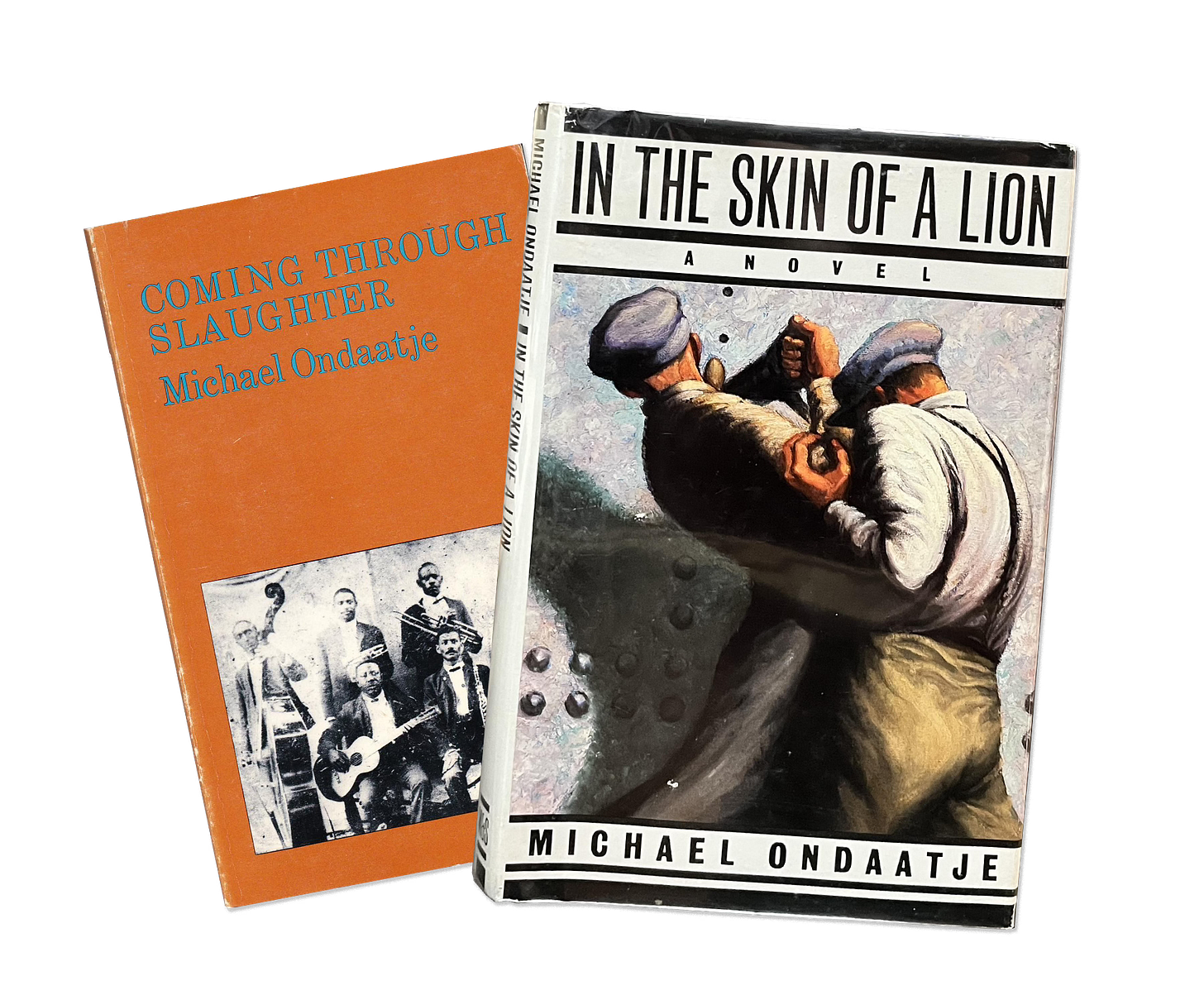

Not pausing to consider, I blurt: “[Michael] Ondaatje. Coming Through Slaughter.”

I did not know this about Mark. It never came up. If it had come up, I would have told him the story I have promised you, dear reader, that I will circle back to. In any event, it was this quote that made me want tell you the story in the first place… or perhaps third or fourth place – still not 100% sure. Just hold onto that thread in your mind.

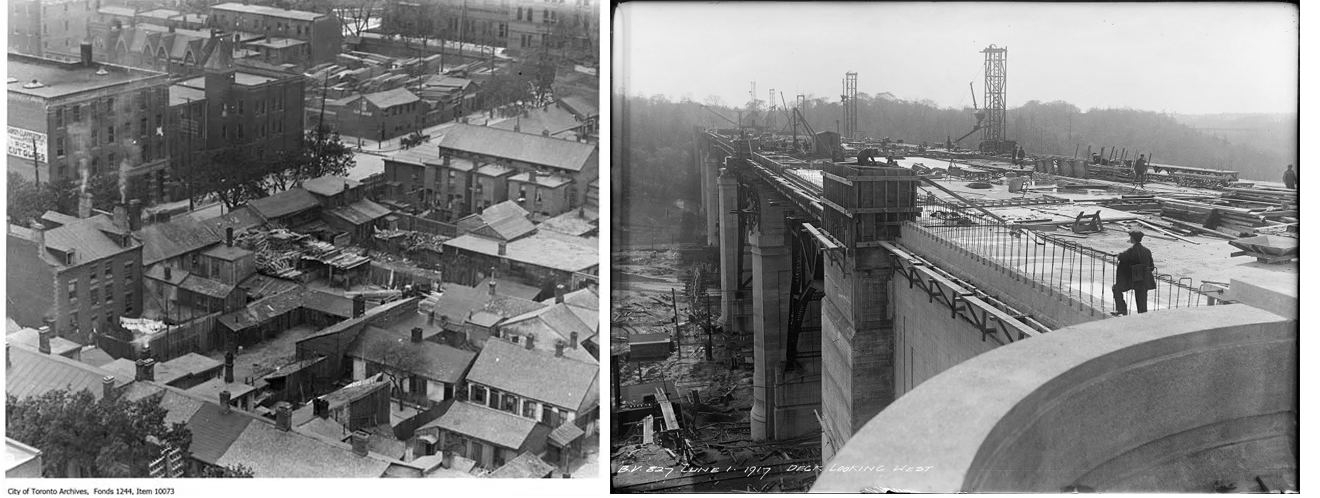

Last Sunday, Sarah and I attended the book launch at the legendary Horseshoe Tavern for our friend Adrian Griffin’s first novel, The Ward. It’s a murder mystery set in the historic St. John’s Ward district of earlier Toronto. From the 1840s to the 1950s, it was the crossroads in the heart of the city – literally in the shadow of Toronto’s old City Hall, which grew in the Ward’s midst, opening in 1899 – where freed slave African-Americans, Chinese railway-building bachelors and the first waves of Jewish, Irish, Italian, Polish and other European immigrants all lived together in a dense, poorly planned and poorly serviced zone that would eventually be demolished to make way for the New City Hall (mentioned in last week’s post #23!), Eaton Centre and Sheraton Hotel developments. In both its polyglot makeup and the official treatment of its residents, it established a template for the simultaneous celebration and neglect of Toronto’s newcomer populations.

Of course, you can’t think of a novel set in the early burgeoning city of Toronto among its hardworking immigrant underclass and not think of Michael Ondaatje’s In the Skin of a Lion, which includes a core storyline involving a Macedonian immigrant working to build the transformative and iconic piece of infrastructure that is the Bloor St. (aka Prince Edward) Viaduct, completed in 1918.

No doubt because he is of a literary bent himself, when Justin Rutledge took the stage at the Horseshoe as part of Adrian’s launch of The Ward, the first of his three-song set was Jack of Diamonds – a song he co-wrote with none other than Michael Ondaatje. That nod to the unspoken connection between the work of his two friends is an act of city building as much as it is of poetry. Elsewhere, Justin does more of it himself with lines like:

“…my tears roll by like taxis / on Bloor St. / at 10 pm / on Friday night…”

– The Suffering of Pepe O’Malley (Part III)

or

“…You're leaning in the doorway / Your dress is like a dark vale [sic] / But I'm not going your way / I'm going back to Parkdale…”

- A Penny for the Band

or simply by naming his first band The Junction 40 after the bus route that serves the neighbourhood he grew up in that’s now my neighbourhood too. Or think of Gord Downie’s reference to the Horsehoe in Tragically Hip’s Bobcaygeon:

“….That night in Toronto / With its checkerboard floors”

That single line resonates with shimmering identifiability for anyone who has ever set foot in the Horseshoe and brings pilgrims from other cities just to see it for themselves. Nothing. Just some simple tile in a plain pattern in not especially great shape in what looks like a regular dive bar. Absolutely loaded with myth and meaning.

Or think of the countless novels and films and TV shows where Toronto isn’t merely a convenient locale or a stand-in for somewhere else but a fecund setting where fictional characters come to life and move through spaces in our imaginations we’ve moved through ourselves in real life and leave their shadows in every nook and cranny of the place. That phenomenon of a place being simultaneously real and imagined, contemporary and timeless, fact and fiction, is what makes a city a rich environment to be in as a resident or a visitor. It’s why literary tours exist. It’s why plaques go up on houses at Queen & River to say “Joyce Wieland lived here”.

The Church of the Holy Trinity was meant to have been demolished with the rest of The Ward but the community appealed to spare it. So there it sits in the small square between the brutalist Bell Trinity office block, Eb Zeidler’s soaring Eaton Centre shopping mall and the adjacent Marriott Hotel, serving a variety of local communities and hosting the Toronto homeless memorial. It too became part of many music fans’ Toronto pilgrimages – some for a legendary early Jeff Buckley performance but most famously for the Cowboy Junkies’ genre-defining live recording, The Trinity Session (1988).

Whether as an exercise of power or out of pure ignorance, it’s possible to look at a city as a collection of assets: buildings, streets, natural features, underground infrastructure, centres of government, business, education, sport and the occasional monuments that reinforce the official story of the powerful. Each of these things can be replaced, renewed, reinforced or abandoned. None of them establish a real sense of place or mean anything beyond time or as elements of connective tissue without the layers of mythology added by artists and citizens who reflect or challenge or reimagine what the city can be – who weave poetry, fiction, music, art and action into the social fabric of the place. This city – or any city, for that matter – is a meaningless collection of stuff without the lifeblood of art coursing through it. This work happens subtly and often invisibly over time but it is critical to the success and vibrancy and endurance of a place.

This is the guiding principal of the Six String Nation project. By shaping dozens of materials from all around Canada into a single, portable, democratized, functioning instrument and making it available to both musicians and regular citizens, I was attempting to layer natural history, official history, local lore, cultural identity, touchstone events, regional characters and varied community foundations into an object that was both abstract and solid at the same time – a repository for existing stories, a jumping off point for new stories and a vehicle for diverse individuals to participate directly and indirectly in the creation of a new, richer, more reflective and responsive layer of world-making on top of and woven into existing notions of Canadian identity. In short, it is an attempt to declare Canada’s diverse identity (indigenous, settler, immigrant, etc.) not as a matter of policy or demographics but of living mythology.

I will never forget one sunny summer day a few decades ago sitting on the patio of the famed Café Diplomatico at the corner of College and Clinton streets with the Ottawa Calabrian poet Antonino Mazza and Ettore Castagna and Domenico Corapi from the traditional Calabrian music collective Re Niliu in town for a visit. As we sat and talked over drinks and snacks, Dave Wall – then of the Boubon Tabernacle Choir – rode up on his bike to say hello. Over the next 20 minutes or so, I noticed Mary Margaret O’Hara walk by, Atom Egoyan paused on the northwest corner deep in conversation with a companion; and crossing on the south side of the intersection, who else but Michael Ondaatje. None of this was noted aloud by Antonino or myself. No other patrons were craning their necks or pointing or shouting for autographs. All of these artists responsible each in their way to adding layers of meaning to our city were simply there walking around with all the other humans making mythology. To me, it was the same as what it must have been like in Greenwich Village when you would not take special note of William Burroughs or Maya Angelou or Alan Ginsberg or James Baldwin making their way to the corner store or stopping at the local watering hole. These days it might be Director X, Catherine Hernandez, Mustafa the Poet and Rupi Kaur passing through some other corner of the city, unnoticed, oblivious to one another’s presence except in the recognition that they and the city belong to each other through the medium of their art.

So, you may have thought that I put a quiet little bow on things there with the image of Michael Ondaatje walking across Clinton St. and maybe you’ve independently come to the conclusion that Michael Ondaatje is the thread on which this whole rambling exercise hangs. But that would seem too faint a fanfare for such a revelation. So let me really bring it home here by returning to the house on Lawton Blvd. near Yonge and St. Clair. These days it’s a law office and may even have been a dentist’s office at one point – I can’t remember. For years I’ve been walking past it near Christmastime for a family tradition that includes Carols by Candlelight at the Yorkminster Park Baptist Church directly across Yonge St. – a Toronto tradition since 1933, followed by dinner at a friend’s house just north of Michael’s on Duggan Ave.

When I first moved out of my parents’ house at age 18, it was actually to house-sit for Michael Ondaatje and his partner Linda Spalding in that house on Lawton Blvd. As I mentioned, I’d attended many events at the house so I knew it pretty well already. Michael had a small but mighty record collection and in the days before carrying music libraries around with you on your phone, that record collection was my source of music that summer. There were many artists in that collection that I knew already – Randy Newman, Tom Waits – but although I was familiar with the name Ry Cooder from various guest appearances on other albums and a few magazine articles, I really wasn’t familiar with his music so this was my crash course, my total immersion into the music of Cooder and I grew to know and love every note on these records.

Years later, I was the production coordinator at Harboufront Centre for the WOMAD Festival, founded in the UK by Peter Gabriel and Thomas Brooman. It was the second or third edition of the festival held in Toronto and the duo of Ry Cooder & David Lindley was the big ticket draw for the final weekend of the festival with Ry’s son, Joachim, joining on percussion. They’d arrived a couple of days in advance to do workshops and hang out so I’d have several opportunities to meet the man I’d first encountered in Michael Ondaatje’s living room. I’d been sent a copy of Ry’s dressing room rider and something on it was unclear. I wanted to make sure we got it right so I found Ry and Joachim sitting on a planter box outside York Quay Centre between performances and nervously went to ask,

“Excuse me, Mr. Cooder, your rider asks for ‘herbal tea’ in the dressing room but doesn’t say what kind. What would you like?”

Ry drawled, “Awww, that’s just something the manager puts in there I don’t know why. I don’t need any of that. Just some water will be fine.”

The ice was broken and I chatted amiably with the two for a few minutes and we got to be genuinely friendly and familiar over the course of the festival, with Ry frequently asking me to remind him of the pronunciation of the names of artists he’d encountered over his few days there – most memorably of Ayub Ogada, the Kenyan nyetiti player, whose performances he enjoyed as much as I did.

It had occurred to me that I should return the favour Michael Ondaatje had done me in giving me the opportunity to discover the music of Ry Cooder, by introducing Ry Cooder to the writing of Michael Ondaatje. And what better book to recommend than Coming Through Slaughter – Ondaatje’s literarily jazz-inflected biographical novel of New Orleans music pioneer, Buddy Bolden – set in the little town of Slaughter, Louisiana near Baton Rouge. It was such a good idea, I thought – making this link – that it lived in my head as just that and I lost track of any recollection of actually putting a copy in Ry Cooder’s hands. Still, it’s the thought that counts, right?

In 1994, I was still in the production coordinator’s role at Harbourfront Centre when Ry Cooder was slated to return for a ticketed outdoor concert with Malian guitarist Ali Farka Touré on the heels of their hugely successful Talking Timbuktu album. Only Touré was called home to Mali to deal with a crisis leaving the gig in jeopardy. The show was salvaged by pairing Cooder up with Shoukichi Kina, an Okinawan artist he’d played with some years before. Frankly, it was a bit of a Hail Mary pass but tickets had already been sold and such was Cooder’s fan base that they really didn’t care who he was playing with. I was once again in charge of securing his tech rider, which included a Roland JC120 guitar amp. And once again I thought of returning the favour of the literary introduction and convinced myself that I’d only imagined giving Cooder a copy of Coming Through Slaughter on his previous visit – so I went out and bought another copy of the book promising myself that I’d actually deliver it this time.

The day before the show, all the rental gear had been delivered safely to the backstage area and Cooder was ensconced at the Admiral Hotel on the other side of the marina. I called him up and said,

“Hi Ry, it’s Jowi from over at Harboufront Centre. Listen, I’ve got something for you and in truth I can’t remember if I already gave it to you last time you were here. It’s a copy of Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter.”

Then came that lovely drawl in reply,

“Oh yeah, sure I remember – you did give me that book. I love that book and I’ve bought many copies over the years to give to friends so if you want to give me another copy, I’ll take it!”

“Great”, I said. “Is there a good time I could get it to you before the show?”

“What are you doing right now?”

“Now’s good for me”, I said – thinking I’d just walk it over to the hotel.

“I wouldn’t mind trying out my amp”.

“Perfect, I’ll head over to the stage and meet you at the back door”.

It was a lazy afternoon, day before the big show, not many people on site, everything ready to go on my end. I went and met Ry at the backstage door and gave him the book. He thanked me and put it in his pocket. He had his guitar and we went inside. I cleared some space, pulled up a chair and plugged in his amp. He invited me to sit and I pulled up another chair. For the next forty minutes or more, we just shot the breeze while he meandered around the fretboard playing snippets of things and adjusting the dials on the JC120. We talked about books and music and kids and boats like we were just two guys and he wasn’t a music legend. It is one of the truly unforgettable moments I had in that space over my years working there (getting hugged by Mavis Staples was another but I’ll save that story for another time). I was glad to have truly closed that circle between two great artists – just as I’m glad to have closed the circle on today’s post. Thanks for holding those threads in place all this time.

The guiding principle of the Six String Nation Guitar. Now I understand why re-visiting the venues is so important for the 20th. A Theme right there in that principle. And as the 17th blog reveals, so much has been added to Voyageur and guitar case over the past 18 years. And will continue to be.